… is a little bit like waiting for Godot. You might be here a while. Maybe you have to finish an assignment, you have to get onto a project, or you need to go out for a run or a cycle. But you don’t feel like it. At all. Thousands of other things are more interesting to you. Vacuuming, emptying the dishwasher, organising your bookshelf by colours, sorting through your pencil or tea spoon collection, online rabbit holes, or <insert your preferred procrastination activity here>. You know you should do it. Maybe you said you would, or you promised yourself you would. But you can’t seem to find motivation to do it.

Welcome to the game of motivation.

She is a tricky old friend.

It is amazing to feel motivated. Tasks seem easier, progress and success seem inevitable when you feel motivated. Often, motivation is high right at the start of a pursuit, and it is also high once you can see the finish line, when it feels like you are almost done. But in the middle, many people experience struggle. That’s when a lack of motivation and a desire to give up is likely the strongest.

And many people give up at this point, which is a shame.

How often have you found yourself in conversations with friends and family about something that someone has wanted to do for a while, and yet, here they are, telling you again that they ‘just can’t find the motivation’ or that they just ‘aren’t motivated’.

Feeling a lack of motivation from time to time is normal and entirely human. Understanding motivation can help you create the conditions to make motivation more likely.

Many people view motivation as something that arrives and something that has to be there before they can act. This is not at all true (or helpful). If you think that motivation is like a bus and you are standing at the bus stop waiting for the motivation bus to arrive so you can get on, I’m afraid you are going to be waiting a while. There is no such thing as a motivation bus.

Instead, you create motivation through action.

Most of the time, action comes first, and motivation follows. That’s right:

Action first, motivation second.

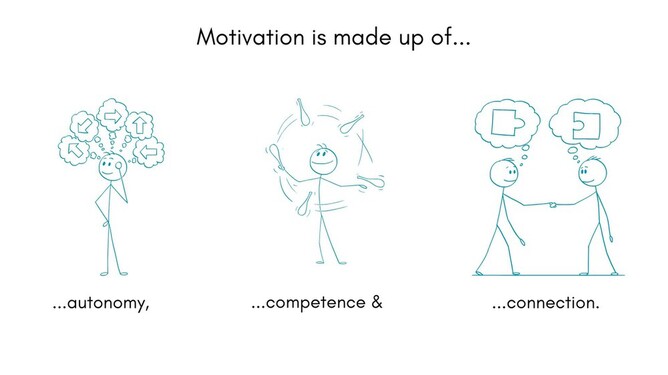

Psychologists Deci & Ryan^ developed self-determination theory, and looking at this theory more closely can help us understand motivation. They suggest that intrinsic motivation is a combination of three particular needs that need to be met to some degree for us to feel motivated. Those three components or needs are autonomy, competence and relatedness. This is in itself interesting, but it also offers you or all of us a starting point for a more detailed reflection on where we might be stuck.

Instead of pondering why you aren’t motivated, why it is so hard to get motivated, and why the motivation bus does not seem to pass your street, you can look more closely at these three components:

Autonomy: This means people feel in control of their behaviour(s) and they are able to direct their actions towards a goal or an ambition that matters to them. They have influence and can make their own decisions.

Competence: People master tasks and learn the skills relevant to their pursuit. Once they have those skills, they are more likely to take action towards their goals or ambitions.

Relatedness or connection: People feel a sense of connection and belonging to others who are pursuing the same thing or supporting them in their ambition.

If you have elements of all three, you are more likely to create the conditions for intrinsic motivation to arise. Note that this may sound straightforward, but it can be quite difficult.

For example, if you think about learning an entirely new skill, say knitting, playing the violin, sailing, etc., initially, you won’t be competent. With your competence low, the other two areas need to balance this out a bit. So you might need strong social connections with others learning with you. And you might need some autonomy in how you develop the skills.

Autonomy is also difficult when your competence is low. Instructors and coaches will be reluctant to let you choose whatever you want, because you might get it wrong and practice in unhelpful ways, or it might simply be too dangerous to let you make all the decisions, because you don’t know what you are doing yet. This is why many coaches will offer you some limited choices at this point. They might give you the two options they know you are capable of; options that match your level of competence. To ensure you feel autonomy to retain motivation, they leave it to you to choose. It creates autonomy. Keep this in mind if you are teaching or coaching complete beginners. They need to dial up connection/relatedness and autonomy because their competence level is low.

If your competence level is high, that is great, though you might get bored easily. If your competence is at the right level to navigate the challenge, but you have someone else interfering, for example, a manager micromanaging or needing to wait for others to complete their part of the work before you can proceed, this will likely feel like a lack of autonomy. This gets frustrating quickly, especially if the frustration also affects the relationships with those people, because that then reduces your connection/relatedness with people. The lack of autonomy will reduce your motivation on its own. It will get worse if it also starts to affect your relationships (= the element of relatedness or connection).

If your feeling of relatedness and connection is high, that is great. If it is low, it can become difficult to create motivation. You might not see the point of applying yourself to tasks because you feel no one cares whether or not you do this well. If you are feeling disconnected and your competence is on the lower end, this becomes overwhelming because you feel like it is all on you and there is no one to support.

You can see how varying levels of the three components impact the self-determination people feel. A sense of self-determination is important to create intrinsic motivation. If you find yourself in a place where you struggle to get motivated, use the three different areas as reflection opportunities.

Instead of asking: Why am I not motivated? Ask:

How much autonomy do I have in completing this task? Why am I doing it, and do I get to decide when and how to do it?

How competent am I in completing this task? What gaps might I have in my skill level? Can I build a few of those skills to make success more likely?

How connected do I feel to those around me who are also in this pursuit? Family, colleagues, teammates, coaches, teachers, etc. How can I influence the relationships with those around me to support creating motivation?

This is also useful to think about if you work with people (kids or adults), especially if you are in a leading role, e.g. coach, teacher, leader, manager, etc. How much autonomy do you give your people? Do they have the competence level they need to complete the tasks you set? And do they feel like they belong?

A reflection like this might reveal where you (or your people) get stuck. Regardless of exactly what you discover during your reflection, remember that it’s action first, motivation second. You will have to take action.

Don’t wait at the bus stop for a motivation bus that will never arrive.

Just a brief word on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: I won’t go into too much detail here, but it is useful to know that motivation is more likely to stick around if you are intrinsically motivated. You are keen to do the thing for reasons that are your own. Let’s briefly look at the definitions:

Intrinsic motivation: you find the activity itself, the process, enjoyable or satisfying without any external pressure or promise of reward.

Extrinsic motivation: you complete the activity because of a promise of an external reward (e.g. money, praise, prizes, etc.) or to avoid negative consequences or punishment, rather than because you inherently find it enjoyable.

So, it is more likely you will sustain motivation over a long time if it is intrinsic. And, if you need more reasons to focus on creating the conditions for intrinsic motivation, Deci & Ryan also explain that people who feel intrinsically motivated show more interest, excitement and confidence, which, in turn, lead to better performance, persistence and creativity.

Sounds good, right?!

Let’s do it, but why?

A good little trick is to get clear on ‘why’ you are doing what you are trying to do. What is your because…? If you find it meaningful to you, it is more likely that motivation will also come to the party.

Take needing to tidy your room or apartment:

‘I need to go for a run.’ - While that might be true, you haven’t given yourself a strong reason to do it yet.

‘I need to go for a run, because I like being outside exercising. It’s fun.’ - This is a clear ‘why’, a clear reason attached to the action you want to take, and it is intrinsic because you enjoy the process of running.

‘I need to go for a run, because I want to get fit or because my coach said so.’ - This also is a clear ‘why’, it’s just not yours or solely focused on the outcome, not the process. So your motivation to do it will be extrinsic, i.e. to please others or to achieve an outcome. Extrinsic motivation is still motivation. (Deci & Ryan distinguish between a few more different layers of extrinsic motivation, if you are interested, read more here.)

You’ll experience both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in life. To be intrinsically motivated to do things feels more enjoyable. Extrinsic motivation is still motivation, it just doesn’t feel as good. Look at the ‘why’ and see if you can make it enjoyable and meaningful. And if not, give it a go anyway. Motivation might still come out to play once you take action…

And remember, if you are waiting for a bus that never arrives… it might be time to start walking.

I hope this is useful and has made you think. If you know someone who might find this one helpful, please share it with them. As always, I’d love to hear from you. Message me on Instagram @mankertina

Key points:

Take action first, motivation follows action.

There are three key ingredients to intrinsic motivation: autonomy, competence and relatedness. If one of them is relatively low, you might need to dial up the other ones.

People who feel intrinsically motivated show more interest, excitement and confidence, which, in turn, lead to better performance, persistence and creativity.

Reflective questions:

What is one thing you have struggled to find motivation for? What is the ‘why’ behind that task? Is it likely you’ll be intrinsically or extrinsically motivated once motivation arrives?

What are some of the activities you are intrinsically motivated for? What would you do regardless of whether you’d be successful and whether people praise or pay you for it?

Whose motivation do you influence? To what extent do you support their autonomy, support and build their competence, and enable their connection to others?

If you’d like to read more about this, start here:

^Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci: Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being