If we trust the internet… and maybe we should not — the average adult makes between 33,000 and 35,000 conscious decisions a day. That includes what to wear, when to brush your teeth, which cup to drink out of, what to have for dinner, and when to go to the bathroom. Many of the thousands of decisions we make are pretty basic, but they take energy, nonetheless.

And then there are bigger decisions that might keep us awake at night for weeks or months while we struggle to decide. Questions and decisions like:

Do we want to buy a house? And which house to buy… and why?

Do I need to break up with my partner?

Do I want to move neighbourhoods/cities/countries?

Do I need to quit my job?

Is it time to tell the other person I love them?

Can I change my career?

Do I want to spend money on travelling or do I want to invest it?

These are much bigger questions with real-life long-term repercussions or, at the very least, consequences.

But let’s look at different types of decisions first.

Easy decisions:

Easy decisions are decisions that you can make without much thought. One of the options is better than the others. For example, if you asked me, ‘Tina, would you like mushrooms or capsicum?’ My answer is always going to be ‘Capsicum’ because I don’t like mushrooms, so capsicum is the better option for me. Easy.

Similarly, if I had the choice between catching up with a small group of close friends for coffee or dinner or going to a large event with lots of people, I would choose the smaller, more intimate setting and event because that is what I enjoy most. If the question is, ‘Would you like to go for a run or a swim?’ I will choose a run. These are easy choices for me because, to me, one option is better than the other.

So far, so easy…

Hard decisions

Hard decisions are made difficult because no option is clearly better (or worse) than the other. Either both options are equally good or bad, or each option has its perks and downsides, but neither is better than the other. Sometimes, either option has some desirable and some not-so-desirable consequences.

For example, you might want to go on holiday and can’t decide between two different destinations because you want to travel to both places; you are equally interested in both.

You might have to decide whether you want to stay in a relationship or whether you need to leave the relationship. You might like or love the person you are in a relationship with, but perhaps there are some things they are not open to doing, and you find it challenging that this restricts your life choices. Or perhaps you know deep down that this isn’t the right relationship for you anymore, but you fear the judgements of others around you, like your families and friends.

Sometimes, career choices can be hard. You might find it difficult to choose what to study after leaving school or what jobs to pursue after you complete university because you have many interests. Heading down one path might feel like closing doors on other opportunities. Equally, you might find it hard to leave a job. You might like the security of having a job and a regular income, but you might dislike the work you are doing or the people you are working for or with. Leaving might feel too scary, even though you know that it is what needs to happen eventually. The idea of doing something new might excite you, but the prospect of uncertainty in between does not appeal to you.

You can already see that harder decisions often have a much longer-lasting impact or consequences, whereas easy decisions might be smaller and more short-term. This isn’t always the case, but frequently it is.

Decision-making, like so many things I have talked about in these blogs, is a skill. A skill that you can practise and get better at. It’s also difficult and can be quite frustrating to learn and master.

There are a few different strategies you can try.

The first step might be to work out whether the decision you are trying to make is easy or hard. That might help you decide because you can ask yourself whether it is worth spending so much time and energy on what should be an easy decision. A frequent example is choosing what you want to order at a restaurant. Some people decide quickly what they want to eat and others take a long time on things that don’t have major significance. If you know that you might find it difficult to decide, you could give yourself a little time limit, e.g. look at all the options and decide within three minutes which option you want.

It can help to work out what makes decision-making so difficult. Will you have FOMO (fear of missing out) if you order something and one of your friends orders something different that might be better? Is it because you want the meal to be a perfect experience, and thus you want to make the best choice? Do you rarely go out for dinner, so when you do, you want to make the most of it? Are you finding it difficult because you feel like you might be judged if you order what you want? It can help to ask yourself what the most important part of this experience is, i.e. is it really about which food you are choosing, or is it more about the company and the conversations you will have while you are out?

Both of these strategies also work with harder decisions. You can set a time limit. With harder decisions, you might give yourself a bit more time, e.g. you might decide now to decide later, say in two weeks. That gives you time to consider all the options and associated consequences. If a decision that needs to be made keeps hounding you, it can also help to schedule or set aside time to think about the decisions you need to make. You can use that time to write a list of possible options and break down what each scenario might look like, what you would need to consider in each case, and who and what else might be affected.

There are other strategies to make hard decisions, one is a values-based approach. To be able to use this, you need clarity on what your values are. What do you value, and how do you want to live those values? You can then use your values as guiding lights towards what is right for you. This may still mean that others are upset about the decision, and it may still mean that you can’t do something you also found interesting, but it does mean you are staying true to yourself. And, importantly, you are acting in line with your values. You choose the option that best allows you to live your values.

Say you value growth and development and are given the choice between going on a trip to a place you have wanted to travel to for a while and pursuing further education; you might choose further education. If you value relationships or friendships and are given the choice to see a family member or friends who live far away, you will likely make time and put in the effort to go and see them, even if this does involve a long drive or is inconvenient to you, because you value spending time with them.

One of the most challenging areas to make decisions about is our relationships: friendships, romantic relationships, and family relations, as well as connections at work. If you find yourself in the scenario I described at the start, you are in a relationship, but you are going through a challenging phase, you can use your values to navigate it. This might mean taking the other person along for a journey through your thoughts, particularly if you value open and honest communication. It might mean admitting that you are unsure where this will lead. Situations like this are difficult if you care deeply for the person, but question whether your expectations of each other and the relationship match. (I will dedicate a separate blog to having break-up conversations because these are a specific challenge.)

An equally challenging decision is needed when choosing where to work and live. You might have a great job opportunity in one place, but that might be far away from friends and family. Use your values to approach the situation. Will a move allow you to grow and develop but compromise your values around family and relationships? Are there strategies that help you manage the downsides of the decision, e.g. could you ring frequently or travel more to visit? Or, if you stay where friends and family are, can you find similar growth and learning more locally?

To make values-based decisions, you will need to know your values. This takes a little time and reflection, but it is worthwhile because your values are your guiding lights in just about everything you are doing.

Another helpful strategy can be limiting your options or asking for help. Instead of looking at all possible options, pre-select two or three options or scenarios and pick between them. A simple example: A few years ago, I needed to buy a new sleeping bag for hiking. I wanted it to be a good one, but I also didn’t want to spend too much time researching and thinking about it. And, because I don’t need to replace my sleeping bag frequently, I also didn’t want to learn too much about the topic. So, instead, I asked a friend, who had recently done a lot of research on sleeping bags, what her top three choices were. When she sent them through, I looked at just those three and then chose the one that was the most suitable for my needs. This streamlined the whole process for me.

It is also useful to write down all possible options. Then, for each option, write down the pros and cons. Once you have your lists, you can prioritise. Go through these lists and see if that helps you figure out which options are best for you. You final choice doesn’t need to be the best option for everyone; it just needs to be a good option for you.

Limiting your options is also useful when you are experiencing decision-making fatigue. Sometimes, we can get so exhausted by the number of decisions we have had to make that we experience this as fatigue. When teaching, I’d go to the supermarket on a Friday afternoon and struggle to decide what bread or pasta I wanted. This meant shopping took longer, and I felt further exhausted. Once I noticed this, I planned my week differently to avoid needing to go to the supermarket on a Friday, or I would go to a smaller supermarket with fewer products to limit my options, which made my decisions easier.

Decision-making fatigue can also occur when you have to make many additional decisions beyond yourself; for example, you make most of the decisions in your household: perhaps you get your kids organised, or you do most of the thinking and prep around meal times. Perhaps you are building or renovating a house, and everyone looks to you for the key decisions and direction. Perhaps you are leading a project at work (or you don’t, but people trust you to have good ideas or the relevant skills), and everyone looks to you. Needing to think for others over long periods can also cause fatigue. So, if you can, redirect some of the decisions you have been making for others back to them.

A word on emotions

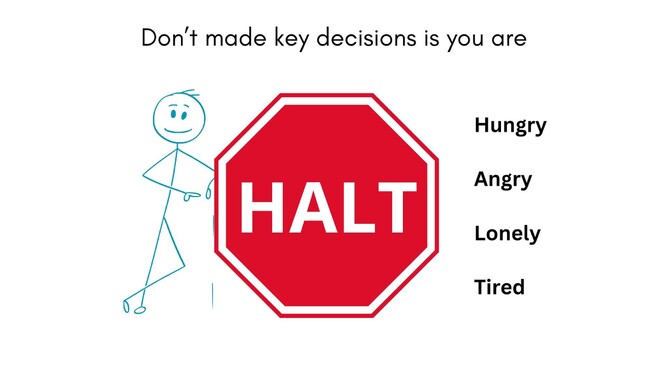

Emotions play a huge role in making decisions, just like they play a huge role in our lives. A good rule of thumb is not to make important decisions while you are

Hungry

Angry

Lonely

Tired

Sad or in pain.

Instead, wait for the emotion to pass (and eat something). Take some time to regulate your emotions and make important decisions after that. Note that this does not mean every decision has to be entirely rational. Our gut feeling is often a useful indication of what we want or don’t want. And we want to make decisions that make us ‘feel’ good, so we might as well consider our feelings.

Keep both short-term and long-term consequences of decisions on your radar. Sometimes, we make decisions in favour of one but don’t consider the other. If you are interested in more on this, read the blog on WIN-WIN.

And, if you are too worried about making the ‘right’ decision and it’s keeping you stuck, consider whether you can make the decision ‘right’ if it turns out not to be ideal.

Keep in mind that not making a decision is also a decision. You are choosing to stay in an uncertain situation. You are choosing to stay in an uncomfortable place. You are choosing to stay stuck. And, potentially, you are choosing to keep others guessing as well.

Every ‘no’ to something or someone is a ‘yes’ to something or someone else.

Every ‘yes’ to something or someone is a ‘no’ to something or someone else.

I hope this blog has been useful and has made you think. If you know someone who might find this one helpful, please share it with them. As always, I’d love to hear from you. Message me on Instagram @mankertina

Key points:

We make thousands of decisions each day - easy and hard ones.

Decision-making is a skill. It can be practised and developed.

There are different strategies you can try to make decisions that are right for you.

Lots of decision-making can lead to decision-making fatigue.

Reflective questions:

What decisions do you currently need to make? Which ones are hard decisions? Which ones are easy?

Which strategies could you try next week?

What are the core values that can help you make hard decisions?