A few years ago, friends and I rowed across Cook Strait, the stretch of water between New Zealand’s North and South Island. It is a fairly treacherous body of water; it’s often very windy and the water gets pretty rough. It was a challenge to pull it off. Naturally, it involved lots of preparation and training. Doing the actual crossing, from Wellington (Mana) all the way to Picton, covering 93 km which took around 11 hrs, is a story for a different day.

One of the reasons we did it, though, was to raise funds for teacher education on emotions and emotion regulation. In collaboration with Victoria University of Wellington’s Youth Wellbeing Study, we aimed to create accessible resources for teachers. We also wanted to provide the information in language that is simple enough to allow conversations about emotions between teachers and students to flow more easily.

Today, I want to share some of the information and language around emotions we have shared with teachers. This blog is adapted from our workbook; I’ll add the link to it at the bottom if you would like to have a read. It includes all references to relevant research. Here, I’ll mainly focus on what emotions are, how they work and why we have them. I’ll share a few specific emotion regulation strategies in a later blog.

Understanding emotions is useful for everyone.

I'll give you a little bit of context first: whether you are a teacher, a coach, a student, an athlete, a leader, a parent, … basically a human being, we all have goals that we want to achieve. These are usually driven by our values. To achieve goals, and live by our values, we need to be able to regulate ourselves and our behaviour. A big part of regulating ourselves and our behaviour is being able to regulate emotions.

For example, often there is a value underpinning our career decisions. Common values that drive the decision to work in education can relate to valuing learning and growth; other values might revolve around health, family, adventure, joy, etc. It helps to know what your values are so that you can use them as decision-making tools, and also so you can regulate your emotions in line with your values. Values lend themselves to specific goals, and achieving these goals requires emotion regulation (e.g. in a teaching or coaching context, regulating your emotions may be useful to remain calm when having to re-explain a concept or movement several times; or demonstrating continuous interest and enthusiasm to foster encouragement and perseverance, etc.)

In that way, emotion regulation enables us all to:

Live in the way we most want to

Behave in a way that best represents the person we want to be

Inspire others to regulate themselves better

Across our workshops and the resources, it has been important to us to emphasise that there are no “good” and “bad” emotions. Labelling emotions as good or bad tends to convey a judgement on our experience as “good”, “bad”, “okay” or “not okay”. We cannot necessarily control our emotional experience: emotions happen as part of being human – and to judge them as good or bad places a judgement on ourselves to change them, when changing them may not be possible or helpful.

Moods are different from emotions. Typically, moods last longer than emotions. Moods can be seen as a particular way of approaching or viewing the world, say with certain expectations, which can determine how situations are interpreted, and therefore how situations are responded to. We have found it helpful to distinguish the two. In a way, moods are like the overall climate, while emotions are more like individual weather events.

Ok, back to emotions.

What are emotions?

Emotions refer to more specific states or feelings (e.g. anger, sadness). They occur in response to particular events. These events can be internal, e.g. a thought or a memory, or external, e.g. someone cuts you off in traffic, you see a cute dog, you’re meeting a friend, etc. They result in particular responses. Emotions are fleeting and research suggests that a single emotion won’t last longer than 90 seconds, unless re-triggered. Many are much shorter.

We can retrigger emotions by staying in the same situation or by simply thinking about a particular situation that has evoked the emotion over and over again. This is useful to know because, most times, you have at least some influence on whether or not you want to stay in the same situation; this depends on whether you would like to keep experiencing this emotion. You can also influence whether you keep thinking about particular situations. Note: you may not be able to control it completely.

Emotions involve changes to our…

…Thoughts

Self-talk

How we think about our experience

…Body

Physiological effects (e.g. depending on the emotion, you might experience increased heart rate, sweating, blushing, increased muscle tension, etc.)

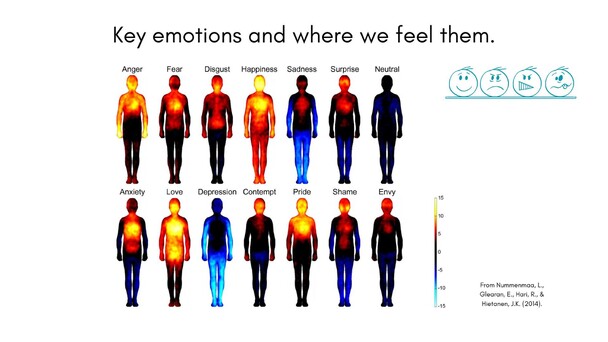

People vary in the extent to which they experience, and are aware of, these physical changes across situations. However, people across cultures and languages feel the same emotions in similar parts of their bodies. Having emotions is a fundamental human experience. So, you are not the only one to feel this way. (See the image & research below.)

It’s important to note that young people experience emotions and the associated body responses to the same degree as an adult (i.e. same intensity when losing a loved one; and when falling in love). However, they do not yet have the experience to be able to understand what this may mean for them. They have less practice in regulating emotions and in managing and preparing for these physiological changes. They also don’t have the history to know that emotional distress, even when very intense, does pass.

…Behaviour

Facial expression

Posture / Body language

Behaviours (e.g. jumping up and down with excitement or slamming doors in frustration).

How we interact with others

Bodily maps of emotions - Have a look at this study, which asked people of different cultures, languages, ages, etc. to indicate where in their body they felt different emotions. (To view the publication, click the image above.) Spoiler alert: people across different cultures & languages reported feeling the same emotion in very similar places in their bodies.

So, in short:

We all have emotions. And they feel pretty similar to all of us.

They show up in at least three different ways: as thoughts, physical feelings, and behaviour (action or inaction).

We also can’t stop our emotions.

And you don’t really want to stop them either. Because it turns out, they are quite useful:

Emotions prepare us for action, e.g. when we need to act quickly (e.g. in danger) our emotional response is hard-wired to get us out of trouble!

Emotions help us communicate, e.g. frowning lets others know we may be confused; smiling lets others know that we want to engage with them.

Emotions deepen our experience of life, i.e. all emotions – including the ones that can be distressing; e.g. sadness deepens our experience. We appreciate the highs in life because we have experienced the lows. Like the ups and downs of a heartbeat, emotions and their ups and downs, are part of life.

So, rather than thinking of emotions as something good or bad, or something that needs to be avoided or controlled, look at them as information worth paying attention to.

The word emotion includes ‘motion’ which means ‘movement’. In many ways, emotions prompt us to move towards things we want more of or away from things we want less of.

Many people we have shared our content with over the years have found it useful to think of emotions as a notification system. Just like your phone has a notification system, we have one too. When you get a notification on your phone, it alerts you to look at a message. The notification itself is not the message. You still need to look at it closely and read the actual message.

Your emotions are very similar. They are the notifications. The message sits underneath them. Emotions alert us to a need we have: I want or need more of this, or less of this. Until we address the underlying need, the emotion is not going away. Instead, we will continue to experience it, just like you would get repeat notifications on your phone. If you don’t regularly pay attention to and address the notifications on your phone, they will stack up. After a while, it becomes difficult to know which messages are the most important ones and which ones you need to attend to first. These repeated notifications start to drain your phone battery.

The same happens to us.

If we don’t attend to our emotions regularly, they stack up and it becomes difficult to work out which ones the important ones are. We struggle to figure out which ones to attend to first and we struggle to address the needs that sit underneath the emotions. Eventually, we feel drained and exhausted. It becomes overwhelming.

Take the time to pay attention to your emotions and see if you can work out which needs sit underneath them. You might have a need for a closer connection with those around you, you might have a need to feel safe, you might have a need to feel respected, you might need some autonomy or independence, or you might just be hungry...

Again, I’d encourage you to pay attention to your emotions. Learn to understand what needs sit underneath each one of your emotions. You can start by noticing where in your body you feel your emotions, what thoughts they come with and how you behave, e.g. when I see chocolate cake, I often think, ‘Yum, I’d like that…’ and I might move to try to get a piece; when I meet one of my friends, I often find myself smiling, and I feel generally comfortable, warm and connected. When I think back to scary or embarrassing moments, I can still feel my heart rate increase or my cheeks heat up. Remember, this is about getting to know yourself and your emotions. This isn’t about judging anything you are feeling as right or wrong. It’s about figuring out your very own notification system and understanding the needs that sit underneath.

So, to put it simply: emotions provide us with information about ourselves, other people, and our environment. We can use this information to make constructive decisions about how we want to act, particularly in situations with heightened emotional intensity. Emotion awareness and regulation are skills. This means they can be learned and practised. Have a go.

In our workshops we’ve shared one final analogy: emotions and our emotional experience are like river rafting – sometimes we have a bumpy patch that feels tumultuous and overwhelming, at other times the ride can feel serene and the flow is easy. Sometimes we can anticipate a bumpy ride ahead and can prepare for it (e.g. over exam and during competition time), at other times the rapids or waterfalls come unexpectedly, as if out of the blue. The best we can do is prepare well for the ride by knowing ourselves, packing our life jackets (emotion regulation strategies), having a good compass to guide us (your values), bringing suitable clothes (prepare & plan), and having knowledge of pit-stops along the way (rest).

I hope this blog has been useful and it’s made you think. If you know someone who might find this one helpful, please share it with them. As always, I’d love to hear from you. Message on Instagram @mankertina.

Key points:

We all have emotions; it’s part of being human.

Emotions are fleeting.

We can’t stop our emotions - but we can get to know them.

With practice, we can learn to understand and regulate our own emotions (and support others in regulating theirs, especially important to be aware of this if you are a parent, teacher, coach, leader, etc.).

Key questions:

Over the next week, pay attention to your emotions:

Where in your body do you feel your different emotions? (e.g. joy, excitement, nervousness, anger, frustration, sadness, embarrassment, etc.)

What sort of thoughts do your emotions come with?

How do you act when you experience particular emotions?

Which needs sit underneath them?

We have shared this content (and more) in workshops at schools and teachers’ conferences, a TEDx Talk, and in our workbook. The information in this blog is based on literature from various authors. You can find a detailed list of references in our workbook.

You can view the TEDx Talk 'Emotions Help Us Create Connection' here.

For a general overview of most of the content in this blog post, please see:

Gross, J. J. (Ed.). (2007). Handbook of emotion regulation. The Guilford Press. Lochner.

Lochner, K. (2016). Affect, Mood, and Emotions. In: Successful Emotions. Springer, Wiesbaden. 12231-7_3;

Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005 May;9(5):242-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. PMID: 15866151.

Harris, R. (2022) The Happiness Trap: Stop Struggling, Start surviving (2nd Edition), Little Brown Book Group: Robinson.

Bodily maps of emotions: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1321664111